Brett Favre wants us to feel sorry for him. He says he’s being unfairly raked over the coals, his reputation tarnished, over a welfare scandal in which he was an unwitting participant.

And now the NFL Hall of Fame quarterback tells us, eight months after the diagnosis, that he has Parkinson’s disease.

That revelation, announced during Favre’s testimony Tuesday before a congressional committee, is sad. Parkinson’s can be a terrible neurological disorder. If his illness follows the course that many sufferers endure, his body movements will steadily deteriorate, as will his speech, and he will wind up bed-ridden and helpless at the end.

It is not surprising, given Favre’s fame and the heightened concerns about brain injuries to football players, that news of his illness deflected attention from what the hearing was supposed to be about — the ease with which a federally funded welfare program can deviate from its stated intent, if those who administer it at the state level are inclined to use it to reward their cronies and aid pet causes rather than to help the poorest of the poor.

It is also not surprising, given Favre’s celebrity status, that members of the congressional panel were more inclined to fawn over the three-time MVP than grill him. They let him give his spin on what happened and presented him as an authority on a program that he claims he had zero knowledge of before he was caught up in what has been described as the worst public fraud scheme in Mississippi history.

To hear Favre tell it, he didn’t know that it was Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) money that Nancy New was funneling to him and a couple of causes for which he lobbied hard. He just knew it was “grant” money.

Maybe so.

But, according to the state’s lawsuit seeking repayment of the misspent funds, Favre was fully aware that the money had strings to it. He knew that it couldn’t be spent on construction projects, such as the new women’s volleyball facility at the University of Southern Mississippi, for which he wanted the money. And he knew that the backers of the project would have to be creative to get around the regulations. That creativity resulted in the $5 million “sham” lease, which, in Favre’s defense, he didn’t come up with and which was signed off on by state officials who should have known better.

What Favre did come up with, however, was a way to get another $1 million from New’s organization, to whom much of the welfare funding was granted, that would cover his personal pledge to the volleyball project at their alma mater. According to his own text messages to New, he proposed in exchange for the money cutting a few radio spots to promote “various state funded shelters, schools, homes, etc.” and he asked that both the amount and the source be kept confidential.

State Auditor Shad White wanted the House panel to ask Favre, during Tuesday’s testimony, why Favre was so concerned about keeping this transaction hidden? It’s a legitimate question. Unfortunately, none of the panel’s members asked it.

Favre claims he’s being persecuted by White as a way to further the state auditor’s political ambitions. He expects to prove it through his defamation suit against White.

There’s no doubt that White is eyeing higher office, most likely a race for governor in three years. And he has milked this scandal for more than his share of publicity and possible profit, having written a recently published book about the scandal.

But it is nonsensical, given the hero worship Mississippi bestows on star athletes, to believe that White calculated he could further his political career by aggressively going after Favre for his share of the tens of millions of dollars in misspent funds. In a popularity contest, Favre would easily outpoint White, scandal or no scandal.

The reason that Favre’s reputation has been tarnished is that he went to the well three times — twice for the volleyball stadium and once for a pharmaceutical start-up in which he was personally invested. He may not have done anything criminal in chasing that welfare money for purposes for which it was not intended. Still, he benefited greatly — until White and others blew the whistle — from a loosely regulated and poorly monitored block grant program that Favre is now criticizing.

He has joined the chorus of those calling for tighter controls because of the questionable spending in every state where the idea of welfare reform — providing education and job training to the poor instead of direct cash assistance — has provided cover for waste and, at least in the case of Mississippi, corruption.

In his prepared remarks at the congressional hearing, Favre said, “Importantly, I have learned that nobody was or is watching how TANF funds are spent. Our laws don’t sufficiently protect against TANF spending unrelated to helping people out of poverty. States have too much flexibility in how they spend this money, which leads to waste and abuse.”

How true all of that is. But also how ironic coming from Favre.

- Contact Tim Kalich at 662-581-7243 or tkalich@gwcommonwealth.com.

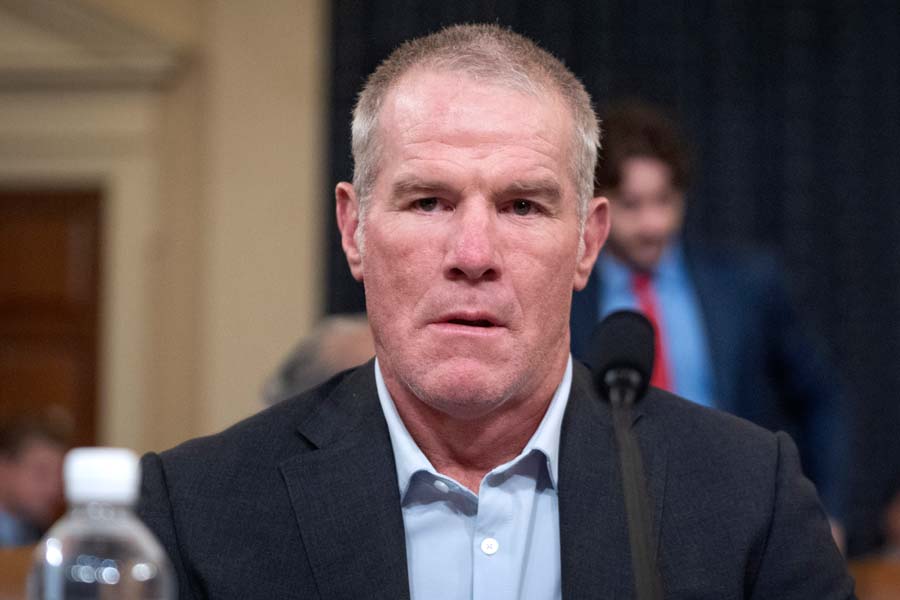

Former NFL quarterback Brett Favre appears before the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means Sept. 24 to testify about Mississippi's welfare scandal. (By Associated Press)

Former NFL quarterback Brett Favre appears before the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means Sept. 24 to testify about Mississippi's welfare scandal. (By Associated Press)